Tick-borne infections are known to be spontaneous. It's no longer necessary to venture into the forest to be at risk. Ticks are migrating en masse to urban forest parks, settling near residential areas, and invading pastures and farmland. The Ixodid family of arthropods is extremely dangerous, and, no less important, it's also the most studied. These ticks are the guardians and, more importantly, the carriers of dangerous pathogens that cause infectious and parasitic diseases in humans and animals. Ixodid ticks have been known to harbor over 300 species of harmful microorganisms, including viruses, bacteria, trypanosomes, rickettsia, and piroplasms.

Content

Ixodid ticks: range, morphology and life cycle

Ixodid ticks are transient, highly specialized blood-sucking ectoparasites of the order Parasitiformes. This suggests that blood plays a crucial role in their survival and reproduction, as they lack other food sources. Representatives of this family belong to the phylum Arthropoda and the class Arachnida.

Currently, about 700 species of ixodid ticks have been recorded (713 were described as of 2012). Sixty of them are found in our country. They are widespread: on all continents and in all climate zones. However, certain species tend to be more prevalent in different regions. For example, the taiga tick is found in Siberia and the Far East, while the dog tick is found in Russia (primarily the European part), Western Europe, and North America. These arthropods are most abundant in the tropics and subtropics.

What do parasites look like?

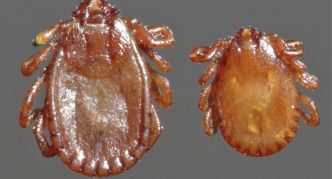

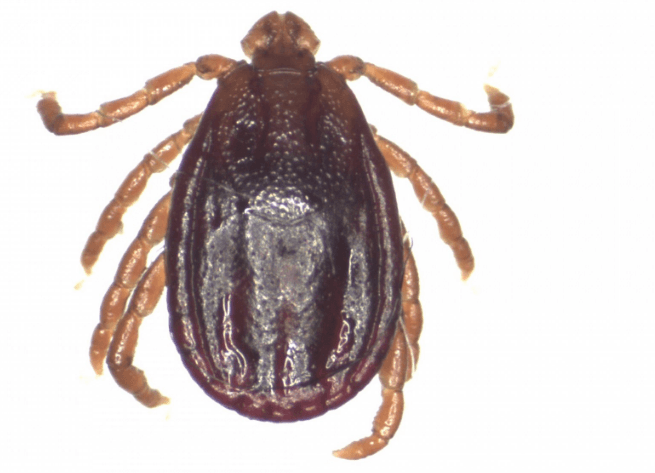

A distinctive feature of members of this family is their large size; a engorged individual can reach 2 cm. The body of an adult tick consists of a trunk (idiosoma) and a complex of mouthparts (also known as the gnathosoma, capitulum, and proboscis). Four pairs of appendages are visible (larvae have three). When unfed, the tick has a flattened, disc-shaped form, tapering slightly toward the anterior edge; when well-fed, it is ovoid.

Ixodid ticks exhibit sexual dimorphism (anatomical differences between males and females). Their dorsums are characterized by different areas of chitinous covering (scutum): in females, it's exclusively the anterior portion, while in males, it's the entire dorsal surface. This dark brown or deep gray scutum is a system of parallel microfolds that unfold as the tick becomes engorged. Size also varies, with females always significantly larger than males. The color of the dorsum also changes depending on the tick's state of satiety. Hungry ticks are predominantly dark in color, brown, and even black, while engorged ticks turn dark blue, yellowish, or gray.

The cutting-sucking mouthparts serve as an anchoring organ, immobilely attached to the body. The main part of the proboscis—the hypostome—is a lower, forward-protruding process armed on the sides with rows of sharp, stylet-shaped, backward-facing teeth. Chelicerae (the jaws themselves) are capable of performing cutting movements, piercing the skin of vertebrates. They spread apart when the hypostome is inserted into the cut wound. A strong grip on the victim is also ensured by the first portion of saliva, which hardens around the proboscis.

The tick's well-developed, segmented limbs are equipped with suckers and setae. These allow the parasite to crawl vertically and firmly attach to the host's body. The setae also serve a tactile function. Most members of the family have orbital eyes.

Stages of development and life cycle

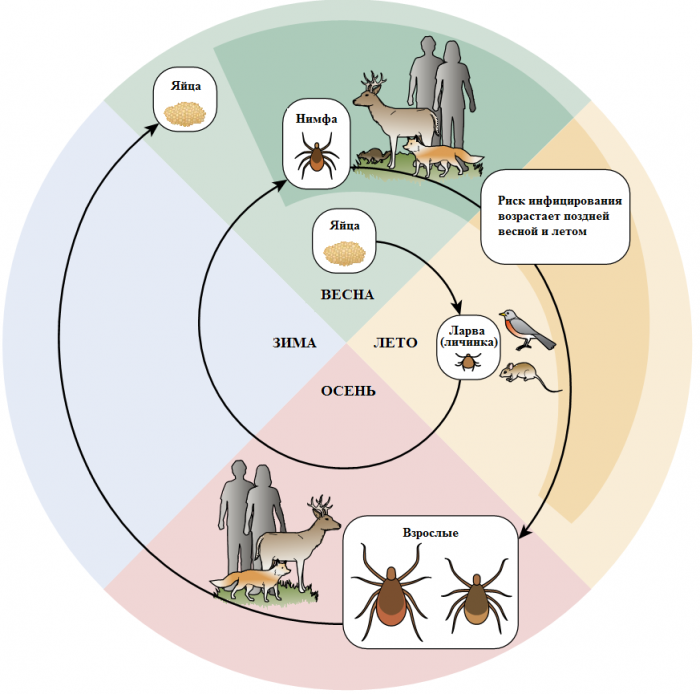

Ixodid ticks undergo a complex development cycle, including egg, larval, nymphal, and adult stages. Individuals in each active phase typically feed once, varying in duration. A short time after satiation, the fertilized female lays up to 17 thousand eggs (not all of them reach sexual maturity). The nesting site varies depending on the species. Based on their parasitic behavior, all ixodid insects are classified as either grazing or burrowing. The former lay eggs in soil, cracks in tree bark, plant roots, etc., while the latter lay eggs in animal burrows and, less commonly, in bird nests. The eggs are oval, shiny, and dark brown. The duration of the egg-laying period depends on the air temperature: at low temperatures, it can last 50–70 days, while under favorable conditions, it lasts no more than 30.

The hatched six-legged larvae feed on small mammals, rodents, and, less commonly, amphibians and reptiles, as well as birds. A single feeding lasts 3–5 days. After molting, the next stage of development—the nymph—occurs. At this stage, the arthropod is significantly larger, and feeding can last 8 days. Then, the larva metamorphoses into an imago (a sexually mature tick). Bloodsucking at this stage lasts from 6 to 12 days, with the period being longer for females.

Distinctive features

Each developmental period is characterized by time intervals of parasitic and "free" existence. Engorged ticks fall away from the host and begin preparing for the next stage in the environment (grass litter, burrows, etc.). These "dormant" periods can last from two months to several years. Thus, the non-parasitic cycle of ixodid ticks is significantly longer.

Ixodid ticks are passive hunters; they can sit on the branches of low trees and in grassy thickets and patiently wait for their prey for a long time. Paradoxically, these sedentary arthropods have no trouble covering vast distances. Most species, when in close contact with their hosts, are even capable of moving from continent to continent. About 20 species of ticks are regularly found near seabird colonies.

Species and genera of the Ixodid family

Most ticks are polyphagous (attaching themselves to different animal species). Depending on the nature of their host relationship, ticks are classified as three-host, two-host, and one-host ticks. The most numerous type is the three-host tick. Throughout their development, the arthropod changes hosts, molting outside the host's body. Typically, smaller animals become their first hosts, while mature individuals choose larger mammals. Two-host ticks undergo their larval and nymphal stages on a single host, after which they drop off to molt and become adults. They then find a new host. One-host ticks feed and molt within the body of a single host.

Photo gallery: family members

- Interestingly, at all stages of development, individuals of the genus Haemaphysalis lack eyes.

- Mites of the genus Dermacentor have a worldwide distribution

- There are about 30 species of parasites of the genus Hyalomma in the world fauna.

- The main prey of individuals of the genus Boophilus is cattle.

- Ticks of the genus Rhipicephalus are very difficult to distinguish from each other, since most of them are similar in appearance.

- The most famous representatives of the genus Ixodes are the taiga tick and the dog tick.

The most famous species

The taiga tick (Ixodes persulcatus) is found throughout the taiga, from the Urals to Primorye, as well as in mixed forests in central Russia. This parasite's active phase occurs in May and June. Its life cycle lasts 2–3 years. Under unfavorable conditions and in the absence of food, nymphs are capable of entering a state of anabiotic hibernation for up to 10 years. These individuals parasitize rodents, domestic animals, birds and are the main carriers of tick-borne encephalitis.

Dermacentor marginatus is a species of pasture tick. This arthropod is native to Europe and the Mediterranean. These parasites can transmit all known tick-borne diseases.

Immature individuals of Dermacentor marginatus settle on livestock and forest mammals, while adults pose a threat to humans.

The dog tick (Ixodes ricinus) is the primary vector of tick-borne encephalitis. It is distributed throughout Russia (including the Caucasus and Crimea), in all coniferous and deciduous forests, and is often found in steppe and forest-steppe regions. Its activity period extends throughout the warm months (April–October), and its life cycle can last up to six years. It is a pasture species.

Immature larvae and nymphs of the dog tick settle on small rodents, birds, reptiles, and adult individuals attack humans, cattle, wild and domestic mammals.

Ixodes pavlovskyi is a species known to transmit tick-borne encephalitis and Q fever. It is native to the Russian Far East, Altai Krai, and Kazakhstan. It is a passive, live-in parasite that attacks various mammals and birds.

Ixodes laguri is a burrowing tick. It spends its entire life cycle near small mammals and rarely attacks domestic animals. It is found in the steppes and forest-steppes of the Volga region and Kazakhstan.

Ixodes apronophorus is a carrier of Q fever, typhus, and tularemia. It is a burrowing species. Its active period is from February to December and it does not attack humans.

Ixodes apronophorus is found almost throughout the entire territory of our country, its favorite places of settlement are swampy forests, taiga, thickets along rivers and lakes

Ixodes (Scaphixodes) signatus is a common companion of birds, particularly cormorants. No attacks on humans have been observed.

Haemaphysalis punctata is a vector of tick-borne typhus, brucellosis, and Crimean hemorrhagic fever. It is active in the spring and fall months, and in some areas, it can attack year-round. It is found throughout southern Russia, Kazakhstan, and Central Asia.

Haemaphysalis punctata often chooses cattle as prey, occasionally small mammals and birds, and also attacks humans.

Diseases carried by parasites

A tick bite isn't a death sentence, but it does carry a risk of infection. The parasites themselves are merely carriers, and relatively healthy individuals can be found alongside infected ones. But what is the likelihood of being bitten by a "harmless" tick? The answer is minimal. By piercing the skin of vertebrates, the parasite injects a portion of saliva, which becomes the main danger for the new host.

It's important to remember: the longer a tick feeds, the less likely you are to survive. Ixodid ticks are involved in the infection of humans and animals, as well as the spread of a number of diseases.

Video: Ticks as carriers of dangerous infectious agents

Tick-borne encephalitis

The vast range of its vectors, their adaptation to various climatic conditions, and the diversity of their hosts (from small rodents to humans) have led to the emergence of numerous strains of tick-borne encephalitis virus. Infection affects the central nervous system, resulting in symptoms such as:

- high temperature;

- chills;

- lethargy;

- loss of orientation;

- visual impairment;

- speech difficulties;

- signs of meningitis (headache, aversion to light, possible paralysis of the limbs, etc.).

The critical outcome is disability or death. The most dangerous species of infected ticks are those from the Far East. Mortality from infection by these arthropods reaches 30%. European strains are significantly milder, with symptoms resembling the flu or going undiagnosed altogether (due to the lack of external symptoms). Infection with tick-borne encephalitis is not always accompanied by direct contact with the parasite. Since the 1950s, there has been an increase in infections in livestock, particularly goats. Animals themselves easily carry the virus but can transmit it through milk. Recommended preventative measures include vaccination, while public prevention includes tick control in habitats, pasture treatment, and careful animal care (bathing, inspections, and use of repellents).

Lyme disease (borreliosis)

Lyme disease is an extremely dangerous infection that affects the joints, skin, central nervous system, and cardiovascular system. Depending on the disease's course, acute, subacute, and chronic stages are observed. Symptoms of borreliosis include:

- chills;

- joint pain;

- fever;

- pharyngitis;

- runny nose;

- hives;

- enlarged lymph nodes;

- conjunctivitis.

Consequences of infection may include:

- encephalitis;

- serous meningitis;

- cardiac arrhythmia;

- myocarditis;

- bursitis and arthritis;

- paralysis;

- myelitis;

- a whole range of other ailments (memory loss, photophobia, sleep disturbances, etc.).

Lyme disease is difficult to diagnose, especially in the absence of skin rashes. There is currently no vaccine.

Q fever

Q fever (Balkan flu, pneumorickettsiosis) is an acute infectious disease caused by intracellular parasites (Burnet's rickettsia). It is characterized by damage to the pulmonary system. The disease begins with myalgia, headache, and a high temperature of up to 40°C. OC. Skin rashes (especially on the face and neck), irregular heartbeat and blood pressure surges are often observed. The prognosis for treatment with timely medical attention is very positive. However, prolonged fever can lead to pulmonary infarction, pleurisy, pyelonephritis, and other complications. Currently, 40 species of ticks, most common in rural areas, have been identified as carriers of the infection. Those at risk include poultry farm workers, farm workers, hunters, and those involved in meat and fur processing.

Hemorrhagic fever

Ixodid ticks also transmit hemorrhagic fevers (Crimean, Omsk, etc.), typhus, listeriosis, brucellosis, and pseudotuberculosis. Tick bites often result in:

- indigestion;

- pneumonia;

- pyelonephritis;

- arthritis;

- arrhythmia and cardiovascular damage;

- allergic reactions.

Piroplasmosis

For animals, the greatest danger comes from infection with microscopic cellular parasites called babesia, or piroplasms. Piroplasmosis affects mammals and is particularly severe in dogs. The risk of infection increases if the animal is bitten by several ticks at once. This disease is characterized by its rapid onset (an otherwise healthy pet literally "burns out" in a couple of days), as Babesia targets red blood cells. A sharp decline in red blood cell count places a terrifying strain on the animal's cardiovascular and pulmonary systems, leading to intoxication (the liver and kidneys are overworked), and blood clots. Early detection is rare, but the key to preventing this problem is increased attention to your pet during tick season (May-June). Decreased energy, refusal to eat, yellow mucous membranes, and shortness of breath are all reasons to immediately contact a veterinarian. Preventative measures, including daily checkups, the use of special repellents, and tick-repellent collars, can help prevent infection.

Tick bite: signs and methods for removing the arthropod

Ixodid ticks are seasonal. Above-zero temperatures and increasing daylight hours are clear triggers for an attack. Ticks choose low bushes, tree branches a meter above the ground, and grass as ambush sites. It is quite difficult to feel a tick bite because of the anesthetic it injects. People often discover this later, when a number of symptoms may have already appeared—dizziness, nausea, fever, weakness. Therefore, after a walk in the forest or park, it's important to simply inspect your skin, particularly the neck, behind the ears, elbows, groin, and knees—all areas with thin, delicate skin.

A swollen, reddened area of skin with a burning sensation is cause for concern. It's not always possible to detect the tick itself: sometimes the tick attaches briefly and then falls off for some reason. If the tick is clearly visible, it's absolutely necessary to avoid touching it with bare hands. There's a high risk of leaving the proboscis under the skin, which increases the risk of tick-borne infections. Immediately after a bite or if you discover a lesion, seek emergency medical attention. If medical attention is difficult to access, you can remove the tick yourself.

When heading out on a hike (and risking a bite), it's a good idea to purchase a tick removal device in advance. Fortunately, modern choices and affordability are readily available. The list of tick removers is quite extensive: Anti-Kleshch, Tick Nipper, Trix Tick Remover, Uniclean Tick Twister, and others. All of these products are safe and easy to use, and some even come with magnifying lenses.

There are several methods, each of which requires careful sanitation:

- A pair of pointed tweezers, iodine, or any other alcohol-based antiseptic will do. Disinfect the bite site and all instruments. To completely remove the tick, grasp it as close to the head as possible and pull vertically, as if twisting it. If the tick ruptures, reapply antiseptic and carefully remove the head with a sharp needle.

- If you can't find tweezers, regular vegetable oil will do the trick. Apply a generous amount to the tick's entire body. After a few minutes, the tick will begin to suffocate and try to crawl to the surface.

- Kerosene works on the same principle. Lubricated with it, the parasite will also weaken, making it easier to remove.

It should be noted that soaking the tick in oil and other such methods are rather controversial, but they are viable in the absence of other options. After removing the parasite, it is important to preserve the tick and contact a qualified specialist as soon as possible.

If a tick bites a pet, prompt treatment is crucial. Therefore, after a walk, you should inspect not only yourself but also your pets. There have been cases of animals becoming infected without contact with the outdoors, with owners bringing ticks home on their clothing. Pay particular attention to the neck, behind the ears, and between the legs. If a tick is detected, the best course of action is to consult a veterinarian as soon as possible.

Preventive measures

A comprehensive approach to tick protection is most effective. To avoid being caught unawares by a tick bite, it's essential to take all precautions, including:

- Proper clothing: light colors, long sleeves and pant legs, high necklines, no bright colors, dark colors, or shorts. Shoes should fully cover the foot (high-top sneakers or boots). A cap or scarf should be worn, and pant legs should be tucked in. Special anti-tick (or encephalitis) suits are available at tourist stores.

- The use of specialized chemicals—repellents (usually available in aerosol form and having a deterrent effect against ticks) and acaricides (sprays and chalks that affect the nervous system of arthropods, leading to their paralysis and death)—is one of the most effective methods of prevention.

- Regular inspection (every 30 minutes) is an extremely important point in tick protection.

- Appropriate behavior: do not climb into impenetrable thickets, do not break tree branches, do not shake them, etc.

Sometimes, despite all precautions, a bite cannot be avoided. Therefore, it's best to consider tick-borne infection prevention. The most reliable way is vaccination (against tick-borne encephalitis), which is valid for three years.

Undoubtedly, ticks are frightening neighbors. But it's important to remember that vigilance and prevention work wonders. When going for a walk in the woods or park, always consider the possibility of a bite. Therefore, it's worth purchasing repellents in advance and carefully inspecting yourself from head to toe.