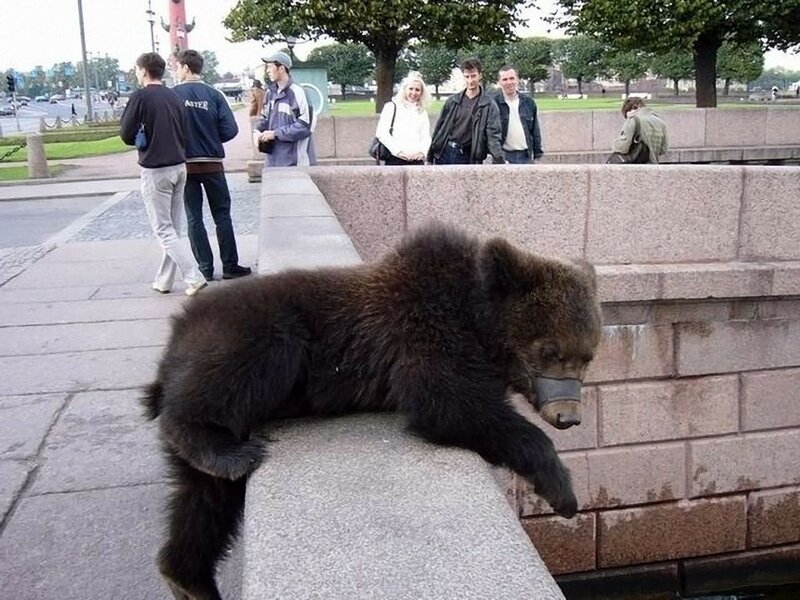

A survey of tourists visiting Russia during the 2018 FIFA World Cup demonstrated the persistence of three popular stereotypes about Russian life: the military runs the country, vodka is the accompaniment to any meal, and bears roam freely in the streets. The last stereotype is the most ingrained, but its prevalence is easily explained by historians.

The Austrian diplomat's book is to blame

Until the early 16th century, Muscovy remained a mysterious land for Western and European peoples. The educated public's understanding of Russian life came from the accounts and notes of merchants, travelers, and diplomats. Information was fragmentary and contradictory. The first book describing the geography, political formation, religious beliefs, and everyday life of Muscovites, "Rerum Moscoviticarum Commentarii" or "Notes on Muscovy," was published in Vienna in 1549. It subsequently became a kind of European encyclopedia of Rus' for diplomats traveling east on embassies, and its author, the Austrian baron and diplomat Sigismund von Herberstein, earned fame as the "Columbus of Russia."

In his "Notes," Herberstein, describing his impressions of a winter journey through Muscovy in 1526, recounts the harsh weather conditions, which even the native population could not withstand. The diplomat notes that the cold that year was so severe that many drivers were found frozen to death in their wagons. Cold and hunger forced bears to leave the forests and attack villages. According to Herberstein, the bears "ran everywhere," breaking into houses. Peasants, fleeing the onslaught of wild animals, fled their villages, dying of the cold "a most miserable death."

The Austrian ambassador's memoirs contain several other descriptions of close proximity to bears. He mentions vagabonds who earned a living by leading bears "trained to dance" through villages. He recounts the amusements of the Grand Duke, who kept bears in a special house for fights, in which men of low rank participated. He recounts an anecdote about a peasant who climbed into a hollow tree for honey and got stuck. Fortunately, the bear, who had come for the forest delicacy, began to climb into the hollow, whereupon the unfortunate bear grabbed hold of him "and screamed so loudly that the frightened beast jumped out of the hollow, dragged the peasant along with him, and then fled in terror."

Whether all these events occurred exactly as the author describes them is difficult to say. But for Europeans, his work long remained a recognized authority on everything related to Muscovy. It was cited by Austrian, German, and Italian scholars and researchers. The book itself, "Rerum Moscoviticarum Commentarii," was reprinted 14 times in the 16th century, in German, Latin, Italian, and English. As a result, the appearance of bears in winter villages came to be perceived as a regular occurrence, characteristic of Muscovy as a whole.

The artists are to blame

Medieval cartographers also contributed to the strengthening and dissemination of the stereotype of “bears roaming freely in settlements.”

The first depiction of a bear on a map of the Moscow Principality appeared on Antonius Wied's map, which he created specifically for Herberstein. The vignette depicts men catching a bear with spears near Lake Onega. The map was published in 1546 and was subsequently reprinted six times as part of Münster's "Cosmographia."

Vida's work had a strong influence on medieval cartography, and the image of the bear became traditional on subsequent foreign maps of Muscovy. It can be said that, thanks to Vida, the bear became the symbol of the Moscow Principality, and later of Russia.

Images of a bear are also present on the map of Olav Magnus, and Francoeur, while creating a map of Mestny Island and the Yugorsky Shar Strait, depicted a bear attack on a member of the expedition, V. Barents.

Bear fun is to blame

Widespread "bear amusements" have contributed to the perpetuation of the stereotype of bears living alongside people in Russia.

In Rus', a popular pastime known as "bear comedy" has been popular since ancient times. It was a circus performance featuring bears, performed by traveling performers. The traveling troupe typically included a bear trainer, known by various names in different regions—"leader," "guide," "bear dragger," a trained bear, a dancing boy dressed as a goat, and a drummer to accompany him. Incidentally, the expression "retired goat drummer," meaning a worthless person, originated from the practice of bear comedies. The musician was often perceived by the people as useless for the performance.

Besides comedies, bears were widely used in Rus' for "bear fights" and "baiting." Bear shows were enjoyed not so much by the common people as by the nobility. They were staged in the Kremlin, at Tsareborisov's court, in country palaces, and in kennels.

Bear fights were also considered a royal pastime. Ivan the Terrible was especially fond of them. Ivan's court had domestic or trained bears, "raced" or semi-wild, and wild ones, brought straight from the forest for entertainment. Under Ivan, these games terrified foreign ambassadors; for example, Albert Schlichting wrote that during a boyar trial, a bear brutally tore one of the plaintiffs to pieces.

It's also known that during the capture of Kazan, a detachment of 20 specially trained bears fought on Ivan the Terrible's side. Bears were also used as smashers to quickly tear down fortress walls or wreak havoc. This is where the expression "a disservice" comes from.

References to "bear games" have survived in Russian literature. In his story "Dubrovsky," Pushkin describes the cruel games of the nobleman Troekurov, who amused himself by setting bears on his guests.

Various forms of bear entertainment were a part of Russian life until 1866, when a decree banning them was issued. Five years were set for the final cessation of the trade. Thousands of tame bears were then exterminated across the country. According to the decree, the owners of the trained animals were obligated to kill them themselves.

Foreigners arriving in Muscovy, and later the Russian Empire, naturally witnessed circus performances, fights, and baiting. The widespread entertainment and subsequent stories about it also contributed to the widespread circulation of stories about "bears in the streets" in Russia.